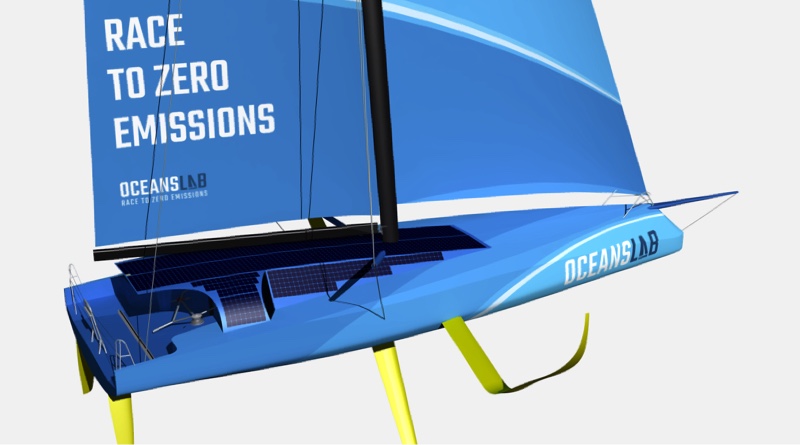

World’s 1st green hydrogen racing yacht aiming for Vendee Globe 2024

The round-the-world Vendée Globe may be the world’s most gruelling sport competition, and the world’s 1st green hydrogen racing yacht is preparing to take it on in 2024 and prove the possibilities and potential of hydrogen as a zero emission energy source.

The entry is being put together by OceansLab, co-founded in 2019 by Phil and Rebecca Sharp with the mission of “accelerating the uptake of high performance clean innovations through the world’s most extreme ocean races.”

Phil is a champion skipper who placed 4th in the 2005 Mini Transat solo race from France to the Caribbean and went on to achieve over 25 podiums in transatlantic and coastal racing, with victories in two Championships. Along the way he also broke three World Sailing Speed Records.

Going hand in hand with his talent and perseverance in sailing has been his dedication to finding better, cleaner energy systems for everything on the water. OceansLab is a member of the Sports for Climate Action initiative and Race to Zero, both of which fall under the umbrella of the UNFCCC – United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – the full name of the group in charge of the Paris Accord and COP conventions.

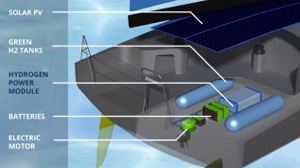

Hydrogen Power Module

In addition to his racing accomplishments, Phil is a mechanical engineer, a co-author for the International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, and works in collaboration with Imperial College London and EIGSI University in France.

In the course of developing the components of the green hydrogen racing yacht, Phil invented a hydrogen power module (HPM) and founded a company, Genevos, to build and market the drop-in plug and play system. The HPMs come in a range of power ratings from 15 kW to 45 kW and can be connected in parallel to provide zero emission power for applications up to 500 kW.

In the course of developing the components of the green hydrogen racing yacht, Phil invented a hydrogen power module (HPM) and founded a company, Genevos, to build and market the drop-in plug and play system. The HPMs come in a range of power ratings from 15 kW to 45 kW and can be connected in parallel to provide zero emission power for applications up to 500 kW.

The fuel cells within the module are PEM (polymer electrolyte membrane) which work similarly to a battery in that they have a positive and negative electrode (+ cathode and -anode), but they are not ‘recharged’, they need a supply of hydrogen from a tank and oxygen from the air.

Cummins.com describes the process this way (video ©Cummins):

When hydrogen comes in contact with the catalyst, the hydrogen splits into protons and electrons. The protons pass through the proton exchange membrane unimpeded and proceed to the cathode side, while the electrons are blocked and forced to travel through an external circuit. As they travel along the external circuit, they provide the electricity needed for auxiliary power or to drive a motor. Eventually the hydrogen protons and electrons reunite and combine with oxygen to produce water.

Chosen for Scottish ferry, Solar Impulse Solution

The Genevos system is designed specifically for marine use – not just in recreational boats but also in commercial operations like ferries and shipping. They were recently chosen by the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC Hydrogen) to be installed for auxiliary power (not propulsion) on the MV Shapinsay Ferry in Orkeney, Scotland.

The module has also been awarded the Solar Impulse Foundation’s Efficient Solution Label. The Foundation is an offshoot of the Solar Impulse expedition which saw Bertrand Piccard and Andre Borschberg pilot a 100% solar powered airplane around the world in 2017. The label is a guide for businesses and consumers to recognize profitable solutions to protect the environment that have been vetted by a demanding evaluation process.

The evaluation of the Genevos HPM details the environmental benefits:

- Produces more than 5X the electrical energy from hydrogen fuel than a conventional diesel generator

- 6 times lighter than lithium batteries storage

- Approximately 85 % of materials can be either reused, reconditioned, or recycled

- 100% reduction in zero greenhouse gas emissions

Around the world with zero fossil fuels

You may be wondering what all this has to do with sailing – after all, isn’t a sailboat powered by the wind, which is already clean energy? Well, yes, but the IMOCA 60 yachts outfitted for the Vendee Globe have significant power demands for things like the navigation console, radar, canting keel, fresh water maker, wi-fi and other communication systems that means an average consumption of 10 to 12 amps per hour.

That electricity has to come from somewhere, and the race has seen a lot of environmentally friendly advances for energy sources during its 32 year history. It’s partly because competitors are always looking for any technical edge, and partly because it is sailing and sailors generally love water and the environment. Hydrogen is part of the next evolution. (See ‘The Colours of Hydrogen’ below.)

That electricity has to come from somewhere, and the race has seen a lot of environmentally friendly advances for energy sources during its 32 year history. It’s partly because competitors are always looking for any technical edge, and partly because it is sailing and sailors generally love water and the environment. Hydrogen is part of the next evolution. (See ‘The Colours of Hydrogen’ below.)

For the first few years of the race, a diesel generator was the only viable way to obtain electricity, then in 2004 French yachtsman Raphaël Dinelli tested a solar panel system and used only 20% of the fuel taken on board – after 4 months of sailing.

In 2008 Yannick Bestaven introduced the hydrogenerator, in which the motion of the boat moving through water spins a turbine to generate electricity. The system was so effective he could have an electric seat heater installed to help use up the excess energy! M. Besthaven then commercialized the technology and co-founded the company Watt and Sea.

In 2016 Conrad Colman installed an Oceanvolt 15kW system that combined an electric motor and a turbine so that propulsion and electricity generation could be achieved with the same unit. His yacht ‘Galileo’ became the first solo racer to complete the Vendée Globe using no fossil fuels at all.

By the time of the 2020 Vendee Globe (won by Yannick Bestaven), 90% of the boats had hydrogenerators and two had electric motors – Alex Thomson teamed up with Oceanvolt and Sebastien Destremau had acquired Colman’s ‘Galileo’ and renamed it ‘merci’.

Hydrogen racing yacht next step in sustainability

For 2024 it is anticipated and almost inevitable that there will be a greater number of fossil fuel free boats. At the very least we know that electric luxury yacht builder Alva Yachts has announced it will be building an entry for the race, and there is the OceanLabs hydrogen racing yacht.

The other inevitable thing is that hydrogen will become an increasingly viable way to provide power for boats and ships – for both propulsion and auxiliary use and for recreational and commercial vessels. We’re seeing it already:

- The hydrogen and wind-powered Energy Observer research ship has been sailing around the world creating green hydrogen from the sea water it travels through to operate a fuel cell storage and propulsion system by Toyota.

- The Aquon One, a finalist in this year’s Gussies Electric Boat Awards, employs a similar water-to-hydrogen system, put to use on a luxury yacht.

- Similarly to the OceansLab and Genevos situation, the Energy Observer has launched a commercialization division, EODev, which is working with Fontaine Pajot yachts to install a hydrogen generator on a Samana 59 catamaran.

- Two giants in marine propulsion – Yanmar and Toyota – are working together on sea trials of a hydrogen fuel cell boat in Japan.

For Phil Sharp the Vendée Globe is not only a round the world expedition but also a life journey that he has been pursuing for decades. On the sailing side, he has been one of the most respected competitors in every class he has participated in, and on the scientific side his determination to reduce emissions on our oceans has resulted in equally admired technical advances in harnessing hydrogen as an energy source.

As he says on his website “Ocean racing is about pushing boundaries in a race to win, however, there is a much greater race at stake: a race to safeguard our planet.” In the months and years ahead we will be sure to follow the progress of Phil, OceansLab and Genevos in both competitions.

The Colours of Hydrogen

While hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, here on earth it is almost always bonded with other elements – as in water, where two hydrogen atoms bond with one oxygen atom to form a molecule of H2O.

There are different ‘colours’ of hydrogen, with the colour referring to the way in which the hydrogen is produced, or extracted, and what it is extracted from.

Separating hydrogen from oxygen in water uses a process called electrolysis which – as the term suggests – requires electricity. When the electricity comes from a renewable source such as solar, water or wind power, the hydrogen is green hydrogen, also referred to as clean hydrogen.

When it comes from nuclear energy it is called pink hydrogen and when it comes from fossil fuel burning generators it is called yellow. There are no shades of yellow in the description, but obviously the dirtier the source of the electricity, the dirtier the hydrogen.

Most hydrogen in use right now does not come form water but is produced by extracting it from natural gas /methane. This is a much more complicated process involving high temperature steam and chemical catalysts and produces carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide along with the hydrogen.

If the carbon emissions and byproducts are captured and stored, usually underground, it is called blue hydrogen. If they are not stored it is called grey hydrogen. The advocates for blue hydrogen say it should be considered carbon neutral, but there is debate about how that terminology is misleading and whether it is just a marketing play.

There is no debate about black and brown hydrogen. They are not clean sources of hydrogen. Through a process called gasification, solid coal or other high carbon material is broken down into its chemical constituents, which includes methane gas – from which the hydrogen is subsequently extracted.

Editor’s note: There is not universal agreement about the definition of each colour. The information here is distilled from: Enapter/H2View, National Grid, World Economic Forum, CNBC.